Andy Rogers takes at look at the telling absence of the Person-Centred Approach in the development of the SCoPEd project.

There is so much to say about SCoPEd that it can be hard to know where to start. Fortunately, many elements of the project – the motivation, methodology, evidence-base, hierarchical structure, consultation process, conflicts of interest and so on – have been closely examined elsewhere, particularly on blogs and social media. So here I want to home in on a few core issues for person-centred practitioners.

Person-Centred Therapy (PCT) has been a major force in the UK therapy landscape since the 1980s. Leading practitioners were influential in the development of counselling services in education and contributed much to the growth of counselling training and professional organisations. The book Person-Centred Counselling in Action (Mearns & Thorne, 1988) is still a core text on many counselling courses and remains one of the UK’s best-selling counselling titles of all time.

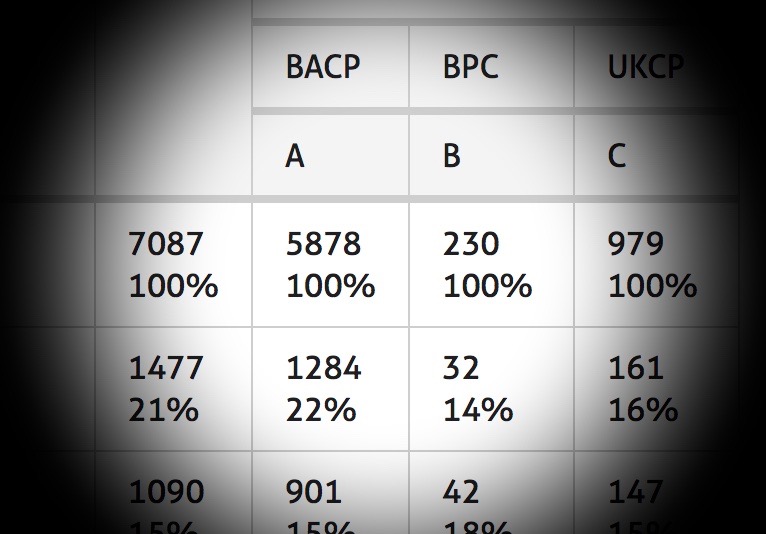

Note that already I am referring to ‘counselling’ rather than ‘psychotherapy’. This is important for the SCoPEd project because its draft ‘competency framework’ explicitly differentiates ‘counsellors’ and ‘psychotherapists’, albeit with a third intermediate category labelled ‘advanced qualified/accredited/psychotherapeutic counsellor’. This differentiation, which the largest professional body involved, the British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy (BACP), had argued previously there was no evidence for, has come in for much criticism; mostly – but not exclusively – from counsellors whose work has been downgraded, with newly qualified psychotherapists defined in the framework as more competent across a range of practice areas.

Inconvenient histories

Before I get side-tracked into the many overlapping issues here – not least around the organisational politics that feed this project – let’s just step back into the world of the person-centred therapist.

In PCT, there is not, and never has been, any meaningful differentiation between counselling and psychotherapy. A contemporary practitioner might be attuned to how others use these terms in a differentiating way and to the tendency for trainings with these labels to meet the differing requirements for professional organisations that cater mostly for either ‘counsellors’ or ‘psychotherapists’. They might also note wryly the way this division operates in the field of employment, with differences in pay, fees, context, status and so on. As Thorne (1999) writes, we need to ‘face the unpalatable truth that the business ethic is all-pervasive… In such a marketplace it is not politic to affirm that counselling and psychotherapy are indistinguishable’ (pp.229-230). Yet, in terms of the therapy itself, i.e. what happens between practitioner and client, there is no substantive case for differentiation within person-centred working.

In the academic literature, the tendency is to refer simply to ‘Person-Centred Therapy’ or to use the terms ‘counselling’ and ‘psychotherapy’ interchangeably. I was going to reference some texts here to illustrate the point but it makes more sense to throw out a challenge: find me a book or paper that articulates the difference between person-centred counselling and person-centred psychotherapy. If any exist, they will still be contradicted by almost all the other person-centred literature.

Much of the contemporary person-centred attitude to these terms has evolved from the position of the approach’s originator, Carl Rogers, who clearly viewed PCT as a form of psychotherapy (just browse his book titles), yet made no distinction between ‘psychotherapy’ and ‘counselling’. As far back as 1942, Rogers was using the terms interchangeably, writing that, ‘intensive and successful counseling [sic] is indistinguishable from intensive and successful psychotherapy’ (Rogers, 1942, p.4, my emphasis). Poignantly for the current debates, the general use of ‘counselling’ for the work of therapy also has its roots in Rogers’s life and work. As a clinical psychologist with no medical training, he made a tactical switch to ‘counselling’ in the mid-1950s in Chicago, when legally the practice of psychotherapy required medical qualifications.

Whatever the pragmatic motivations at the time, it is important to note that the person-centred approach was already becoming a direct challenge to the hegemony of the medical model (and would continue to be so, with increasing vigour and depth), so the switch also made sense politically and philosophically. Clearly, 1950s Chicago is a world away from the UK in 2019, but it is interesting how relevant this moment remains, how the terms continue to have a political potency: are contested, subject to claims of ownership and find themselves jostled into a status hierarchy that serves the interests of those who already have more power in the field by bolstering their portrayal of superior legitimacy, skill, depth or competence.

And there is another more recent historical nugget to unearth here too, which is that PCT’s association in the UK with ‘counselling’ rather than ‘psychotherapy’ could easily have gone the other way. In the early 1980s, as the United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP) developed in parallel with the BAC (then without the ‘P’ for psychotherapy), the person-centred approach had not yet established national organisational representation. So, as Mearns & Thorne (2000) write, there was,

‘no institutional process by which the approach could be involved with the developing professionalisation of psychotherapy/counselling. The result was that the work of engaging with professional organisations was left very much up to individuals, […] person-centred specialists [who] made the pragmatic choice of investing their time in BAC.’ (p.26)

Importantly, the decision not to go with UKCP was not made because PCT failed to qualify as ‘psychotherapy’. In fact, ‘it was only small matters of difference which inspired this choice’ (ibid.), mainly around personal therapy requirements and the approach’s potential positioning within UKCP’s humanistic section.

This alignment with BAC(P) would inevitably lead to an association with ‘counselling’ rather than with ‘psychotherapy’, so it is intriguing to wonder about how the field would have looked had PCT found its professional home within UKCP instead. Who knows how the approach – and indeed UKCP – would have evolved? But the SCoPEd project washes its hands of these inconvenient histories and their attendant complexity and illuminating angles.

Undoubtedly times have changed but PCT has never reneged on its philosophical, political and practical position in relation to ‘counselling’ and ‘psychotherapy’. As one of its leading thinkers in the UK has argued, the case for differentiation – inseparable as it is from professional politics – demands close scrutiny:

‘there is no essential difference between the activities currently labelled “counselling” and “psychotherapy”… [T]o suggest that there is is the result of any one or a permutation of the following: muddled thinking; a refusal to accept research evidence; a failure to listen to clients’ experiences; a lust for status; needless competitiveness; power mongering; a desire for financial gain; or some other unworthy motive prompted by professional protectionism.’ (Thorne, 1999, p.225)

Maps and missing territories

The fact that one of the most established therapeutic traditions in the UK has a lot to say on these matters – not only differentiation but manualisation and professionalisation generally – has been of such little interest to the SCoPEd project that there was no PCT representation on the teams tasked with developing the framework. Even the humanistic modalities more broadly were grossly underrepresented in the Expert Reference and Technical Groups, which were dominated by psychoanalytic practitioners. Statements from BACP following the outcry amongst members about this blatant bias have made small admissions that they got some of the language wrong and were endeavouring to recruit new people to better balance the team.

But how can this have been so overlooked at the outset? What does it say about a project which wants to ‘map’ the world of counselling and psychotherapy that it would erase a whole continent of thought and practice and then, when the inhabitants are outraged, desperately try to patch things up with reassurances that they are ‘listening’ and want to get it right?

What does it say about a project which wants to ‘map’ the world of counselling and psychotherapy that it would erase a whole continent of thought and practice?

Why has the person-centred approach been ignored in this way? Perhaps part of the answer lies somewhere in the SCoPEd organisations’ uncritical embrace of a ‘competency framework’ methodology derived from UCL’s manualisation of CBT for the IAPT project (IAPT, 2007; Roth & Pilling, 2008). While these frameworks might have some uses, it is difficult to understand the perception of the supremacy of this specific method for resolving difficulties in the field and promoting the profession, unless you actually want to bulldoze nuance and erase complexity in order to ‘clarify’ things. But BACP especially seems heavily invested in this approach, having already used it to create frameworks for a range of practice areas (including, it should be said, an IAPT-compliant, manualised version of PCT). Indeed, the organisation is so attached to the Roth & Pilling methodology that in a statement in Therapy Today, the Chief Professional Standards Officer and Chair of the SCoPEd Technical Group, Fiona Ballantine Dykes, claimed that the alternative to developing the SCoPEd framework is ‘doing nothing’ (Therapy Today, May 2019, p.51).

Given this single-minded, blinkered commitment to the competency framework process, it is hard not to conclude that person-centred perspectives – with their critical takes on both the manualisation of therapy and the associated alignment with healthcare values and medicalisation – are simply too awkward, too inconvenient, too damned political. As if a project like SCoPEd could not be political! As if, in its much-trumpeted spirit of collaboration between competing organisations, it could magically transcend all the history, politics, power struggles and diversity of thought and practice in order to objectively ‘map the competences’ of ‘counsellors’ and ‘psychotherapists’, without in the process distorting the field to shoehorn it into such a simplistic hierarchical structure.

I am not suggesting a deliberate conspiracy here, more that a number of professional interests converge around the adoption of these frameworks, whose politically expedient effect – in the apparent coherence of their efficiently organised categories and columns – is to eliminate awkward truths, not least in the profession’s sales pitch to governments and the NHS.

From this perspective, the SCoPEd project is so full of holes that, in one sense, it is hardly there at all. Part of me wonders whether, for all the fanfare and controversy, it will end up – like so many other documents – parked on our hard-drives or floating in the digital cloud, read more than once by almost no one outside of the organisational players, ignored by most of the public, of little interest to potential clients, perhaps skim-read by other stakeholders in the mental health field and then… what?

Well, it is how these things linger on the edges of awareness that says something about their potential power, about how – once installed – their unspoken values seep almost unnoticed into all sorts of areas of our lives as therapists (practice, training, supervision, organisational procedures, government policy). In person-centred terms, they begin to form a hard-to-grasp but nonetheless influential set of conditions of worth for therapeutic practice, which further externalise our professional loci of evaluation.

This is particularly problematic for PCT because, as I wrote in my own submission to the BACP consultation, the draft SCoPEd framework is alarmingly ignorant of person-centred working. Some of the exclusively ‘psychotherapist’ competences, for example, are almost the bread and butter of person-centred therapeutic relationships, which in the real world are often engaged with under the banner of ‘counselling’. Check out 3.5.c:

Ability to negotiate issues of power and authority experienced in the inner and outer world of the client or patient as part of the therapeutic process.

As I say in my response, for person-centred counsellors this would be a central principle of everything they do. Yet ‘qualified counsellors’ are deemed only to have the:

Ability to recognise and understand issues of power and how these may affect the therapeutic relationship.(3.5)

They are perceptive but passive witnesses to issues of power, which for me edges into an unethical disavowal of both the potential impact of their role and the asymmetry of the therapeutic encounter.

Read on and we find that only trained ‘psychotherapists’ have acquired the:

Ability to evidence reflexivity, self-awareness and the therapeutic use of self to work at depth in the therapeutic relationship and the therapeutic process.(5.1.c)

Which, again, is at the very heart of person-centred working (e.g. Mearns & Cooper, 2017). Yet ‘qualified counsellors’, we are led to believe, have only an:

Ability to demonstrate a commitment to personal development that includes self-awareness in relation to the client or patient to enhance therapeutic practice. (5.1)

Elsewhere, other competences make ‘psychotherapist’ the sole territory of those who lean heavily towards medical or psychoanalytic thinking, e.g. Ability to demonstrate the skills and critical awareness of unconscious process (3.10.b), which further alienates and excludes person-centred therapists.

Language barriers?

In response to the criticism attracted by the draft framework, BACP has suggested it will attempt to iron out some of these issues with language tweaks in future iterations, but such errors are extremely revealing of the way the unique theory and practice of PCT is invisible in the project, subsumed and submerged within generic statements around counselling practice while its more challenging perspectives have been redacted or just ignored into oblivion.

In any case, we should be wary of the reassurances from the SCoPEd teams that they just need to get the language right. For one thing, this smacks of PR rather than full engagement with the critiques (as in the infamous politician’s or corporate CEO’s defence, “I misspoke”). Furthermore, in this focus on language, BACP et al seem (wilfully?) to misunderstand the various challenges and objections, which are not only about words – as if swapping them with others would make it all better – but rather see language as the most obvious manifestation of deeper flaws in the project.

Something else I find troubling here is my own personal experience of having the same conversations with senior individuals at BACP about another competency framework, one drawn up for university and college counselling in 2016, which I had criticised as inappropriately redefining the sector as a branch of manualised healthcare (Rogers, 2019). In a face-to-face meeting and follow-up emails, it was acknowledged that BACP did not ‘get the language right’ and I was offered reassurances that this would be taken on board for future frameworks. Yet here we are again. I have no idea what the people I spoke with took away from our chat but somewhere in the subsequent organisational processes these reassurances evaporated into nothing and PCT once more finds itself ignored and excluded.

The person-centred approach, arguably, is not blameless in all this. Perhaps we have not been great at organising; perhaps we have felt so compelled to make concessions to the dominant narratives in ‘mental health’ and the therapy professions that we have our lost ourselves a little along the way, woozy with disorientation and gripped by a fear of judgement if we defy the trajectory of our own field. Nevertheless, the fact that a voice speaks with less assertiveness amid the noise of our culture’s deepening conversation with psychological distress is no excuse to ignore it, and it is troubling – and disturbingly ironic – when therapy organisations fall into this trap.

Perhaps my own tiny sketch of PCT’s political difficulties does it a disservice too. While I have drifted away from person-centred forums (journals, organisations, conferences etc.) over the years, social media – for all its flaws – has reminded me recently that there is a vibrant community of practitioners out there and PCT still has a unique and vital contribution to make to our field, to ‘mental health’ thinking generally and to our culture more widely. As ever, what the person-centred approach has to say is not always easy listening for those with professionalising aspirations and intentions, but surely it is our job as therapists to hear the things that others cannot bear, to listen to the most difficult truths, to welcome their complex, quietly spoken messages, to meet and fully engage with the challenges they present – why can’t our organisations do the same?

Tipping point

As I researched the background to PCT’s early alignment with counselling and BACP (as discussed above), I stumbled across another passage in the same book (Mearns & Thorne, 2000) that, although written in my early days as a person-centred therapist twenty years ago, rings as true now as it did then:

‘It would be a tragedy… if person-centred therapists lost heart at this stage when, precisely because of some of the unfortunate moves towards a sterile professionalism… there is a greater thirst than ever among therapists and would-be clients for an engagement with what is truly human’ (p.218).

Whatever happens as SCoPEd ploughs on, we urgently need to find our voices. There are shifts in the mental health sector across disciplines and hierarchies. The medicalisation of distress, the dominance of biomedical psychiatry/pharmacology, the related mechanisation of therapy as another manualised treatment for discrete psychological ‘disorders’ and its subsequent co-option by the State in health and welfare policy are all coming under increasing pressure from a range of critical standpoints.

We may be at a tipping point. The more people experience this rigidly medicalised ideology in practice, the more they become aware of a need for something else and actively begin to seek it out. With IAPT’s legitimacy crumbling (Jackson & Rizq, 2019), the promises of psychopharmacology unfulfilled and psychiatric diagnosis itself falling further into disrepute, it is starting to look as if Person-Centred Therapy was on the right side of history all along.

Our professional organisations might want to listen more closely to what we have to say; not to assist their PR blitz around contentious projects, but to reset the course of the professions in ways that more authentically respect and promote the core values and diverse perspectives found in our field’s rich ecology of practitioners.

Andy Rogers has been a BACP member and counselling service coordinator in further and higher education for 20 years. He also works in private practice in Basingstoke, Hampshire.

References

IAPT (2007) The competences required to deliver effective cognitive and behavioural therapy for people with depression and with anxiety disorders. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/drupal/site_pals/sites/pals/files/migrated-files/Backround_CBT_document_-_Clinicians_version.pdf (accessed 05 July 2019).

Jackson, C & Rizq, R (2019) The Industrialisation of Care: Counselling, Psychotherapy and the Impact of IAPT. Monmouth: PCCS Books.

Mearns, D & Cooper, M (2017) Working at Relational Depth in Counselling and Psychotherapy. 2nd edition. London: Sage.

Mearns, D & Thorne, B (1988/2013) Person-Centred Counselling in Action. London: Sage.

Mearns, D & Thorne, B (2000) Person-Centred Therapy Today. London: Sage.

Rogers, A (2019) ‘Staying Afloat: Hope & Despair in the Age of IAPT’ (pp. 142-155) in Jackson, C & Rizq, R (2019) The Industrialisation of Care: Counselling, Psychotherapy and the Impact of IAPT. Monmouth: PCCS Books.

Rogers, C (1942) Counseling and Psychotherapy: Newer Concepts in Practice. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Roth, AD and Pilling, S (2008). ‘Using an evidence based methodology to identify the competences required to deliver effective cognitive and behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety disorders.’ Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36, pp. 129-147.

Thorne, B (1999) ‘Psychotherapy and counselling are indistinguishable’ (pp. 225-232) in Feltham, C. (1999) Controversies in Psychotherapy and Counselling. London: Sage.

*

You must be logged in to post a comment.