by Denis Postle

Sometimes there are projects that in their obtuseness, their folly, and their slippery language, do harm to the human condition. The Scope of Practice and Education framework (SCoPEd)1, the creation of three of the dominant UK psychopractioner organisations, is one of them.

SCoPEd shines a bright light on the activities and supposed validity of the British Psychoanalytic Council (BPC), the United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP) and the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), and claims to have synthesized a catalogue of standards for the practice of counselling, psychotherapy and psychoanalysis. But spotlighting casts a shadow and SCoPEd, with its recent formal adoption, is no exception – it excludes and demeans countless other viable forms of working with the human condition in the UK.

After two books 2,3 and many articles on therapy regulation 4, 5, 6, 7 and 28 years as a continuing participant in the Independent Practitioners Network (IPN) 8 – an antidote to earlier attempts to regulate UK psychopractice – and publishing the eipnosis website 9, I had given up speaking from the regulationist shadow. Except, if direct government control or legalised titles were to emerge. SCoPEd isn’t that, but it points in that direction.

And this is why SCoPEd is a problem. No, worse than a problem, offensive. Younger practitioners may not be aware that SCoPEd is only the latest in close to a quarter of a century of attempts to professionalize their delivery of working with the human condition in the UK, with the barely hidden aspiration of seeking state endorsement of this status.

It was offensive, two decades ago, to sit opposite Anne Casement, the then chair of the UKCP, in a BBC Radio 4 studio,10 declaiming that:

“At the moment, we’re a voluntary register but we are now in the process of moving to registration by law, to statutory registration, we’re actually in the process of doing that… We’re seeking to protect the title of ‘psychotherapist’, so after that, once we’ve registered by law, anyone who calls themselves a ‘psychotherapist’ will have us to deal with”. (Casement 1999)

Other senior therapy practitioners claimed that there was a need ‘to rid the psychotherapy garden of its weeds’ 11. At a Parliamentary hearing about Health Professions Council regulation, I heard someone behind me describe non-compliants such as myself as ‘charlatans’.

Numerous authors and activists pursued opposition to the ambitions of professionalized counselling and psychotherapy. 12,13,14 See also my 2007 book Regulating the Psychological Therapies: From Taxonomy to Taxidermy (mapped, measured, captured and stuffed?)2 , the title of which continues to encapsulate 16 years of the antecedents (and likely result) of SCoPEd.

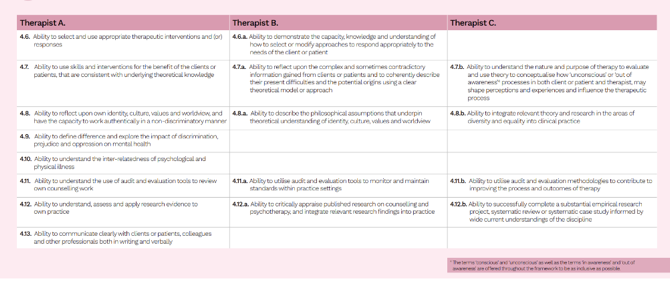

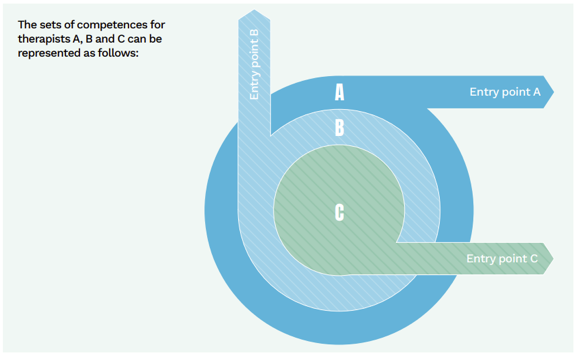

If you are as yet unfamiliar with SCoPEd, three previously warring factions 15 in the UK psychological demographic – BACP, UKCP, and BCP – got together to enable them to become a closed shop in the provision of psychotherapeutic services in the UK. SCoPEd developed three areas of ‘expertise’ and ‘competence’, to represent the claimed capacities of – respectively – counsellors, psychotherapists and psychoanalysts.

In the latest iteration, the three columns have been neatly scrambled to blur this exclusivity, an arrangement that also softens the ascension of BPC psychoanalysis to the heights of psychopractice insight and expertise, leaving BACP members to occupy the prairies of mere counselling.

So what is wrong, mistaken, or harmful about SCoPEd?

Let’s start with it as a taxonomy – describing and circumscribing instances of life and organising them into hierarchical categories.

The SCoPEd taxonomists looked at the practice of the three distinct, and to some extent, antithetical professional organisations, and came up with a hierarchical array of ‘standards’ and ‘competences’. This does two kinds of harm: it does violence to the need for sufficient varieties of caring response to the miasmic diversity of the human condition; and its exclusivity invalidates the many other ways of working with people, as though Co-counselling, Reiki, Sacral cranial, The Alexander Technique, hypnotherapy, Lacanian analysis, massage, breathwork, birthwork, yoga, meditation, dance therapy, EMDR, animal-assisted therapy, horticultural counselling, aroma therapy, sand tray therapy, mindfulness, acupuncture, reflexology, didn’t exist.

SCoPEd diligently explored the professional walled gardens of BACP, UKCP and BPC, and sought and claim to have discovered a legitimate catalogue of psychopractice ‘standardisation’. Apart from making public and underlining the value of the three psycho-professional institutions, what is this for? Isn’t it primarily trying to make them ‘plug and play’ compatible with the NHS and other institutions that hire psychopractitioners? Not least an increasingly privatized NHS. And let’s not forget the 19+ UK universities and the many higher education institutions that run psychopractice courses; for them and the core group of therapy and counselling trainings, SCoPEd’s standardization of psychopractice is happily resonant with the examination/audit culture that infects too much of education.

In The Administration of Fear 16 Paul Virilio speaks of his WW2 childhood experience in Nantes of living under German rule. There were three ways of coping with it, he says: Occupation, being compliant, making the best of it; Cooperation, actively supporting the occupation; and Resistance, acting to derail or stop it.

I see the gilded credentials of the 75,000 practitioners that support the SCoPEd enterprise as a form of ‘occupation’ of the UK psychopractice demographic. It demeans and excludes. And there seems little doubt this patronizing of the ‘inferior’ is what is intended. While there has been significant disquiet about the ‘occupation’, there does seem to have been too much ‘making the best of it’ and not enough ‘resistance’.

Is it tolerable that the nuances of love, of flourishing, of rapport and presence seem absent from the standards? Will they also be absent from future generations of work with clients?

Is this too strong? I think not. SCoPEd is coercive and prescriptive, the best that could be distilled from warring tribes, built via conversations that we might suspect were conducted in Russian ‘vranjo’ mode: “We know that SCoPEd is ethically dubious”; “you know that we know”; “we know that you know but we all keep pretending it is OK”. But is it tolerable that the nuances of love, of flourishing, of rapport and presence seem absent from the standards? Will they also be absent from future generations of practitioner work with clients?

Some psychopractice organisations have voiced opposition to SCoPEd 17,18 but there doesn’t appear to have been a coalition of the excluded. SCoPEd partners commissioned an Impact Assessment, 19 it acknowledged that there was scepticism of the value of the framework but insufficient to derail adoption by the three principal partners, or to deter the National Counselling Society, Human Givens, and the Association of Christian Counsellors joining it for the ride.

The fundamental flaw of SCoPEd, as a protocol promoting a service industry, is that it does nothing to mitigate or even address, practitioner abuse of clients. It leaves clients as the default quality controller; defective practice is identified when someone complains. It doesn’t include what clients need to feel safe – active practitioner engagement with civic accountability. Do other practitioners who know us well personally, stand by our practice? Would they send us clients? And not least, is there ongoing peer assessment of our ‘presence’ and our reputation, that comes with sustained contact?

Sadly, once qualified, a SCoPEd practitioner can keep up a subscription to their regulation club, occasionally dip into CPD, and discuss clients with a supervisor but otherwise avoid reciprocal exposure of their vulnerability with peers. So far as we avoid sharing with peers where we are in our lives, changes in the quality of our ‘presence’ and ‘rapport’ that would merit support, and perhaps challenge, are likely to remain out of sight. These are qualities that appear to contribute more to beneficial outcomes than MA’s, degrees or diplomas 20. The high price of the ‘qualifications’ that entry to SCoPEd requires may justify a paywall for access to psychopractice but for clients looking for a practitioner who can be trusted with their concerns, or their distress, they can often be an inadequate long-term quality guide to practitioners.

The SCoPEd collection of psychopractitioners are people who we might suppose are aware of the social implications of how power and privilege is distributed, of how it can become fossilized, and who are supposedly sensitive to the infinite varieties of grief, fear and anger we may feel. And while mortgages, as a colleague reminds me, may have a significant influence in these matters, how can they submit to their occupation by the SCoPEd catalogue of ‘standards’?

Beyond its politeness, there is something gross about SCoPEd.

Off the page but successfully expressed in the SCoPEd protocol, is the long-standing determination of psychoanalysis to dominate the psychopractice field; how can this illustration of competencies below not be seen as showing ‘C’ (psychoanalysis) as being on top?

And aren’t dominion and its counterpart, subordination, very common client agendas? So how come the flag of psychoanalytic dominion that SCoPEd waves over the enormous UK psychopractice demographic, is acceptable and even cherished by its exponents? Related to this psychoanalytic dominance, is the extent to which SCoPEd, in its apparent drive to open access for psychopractice to the NHS, mirrors/mimics the pyramidal medical establishment, of which psychiatry, a key product distribution arm of Big Pharma, is the dominant, scandalous 21 partner.

Off the page even further, alongside all these reasons for rejecting SCoPEd, there is a perhaps an even more fundamental reason for scepticism. Chasing the wraiths of regulation, and reflection on my own practice, led me to see that, along with other aspects of our threatened civilisation, psychopractice has the form of an extractive industry.22 People meet with psychopractitioners to have their distress or concerns attended to, and across generations of these encounters, from what we have learned with clients, practitioners have extracted a theory and practice base. Clients and trainee practitioners buy this accumulated knowledge and practice as a service but it could and perhaps should be more freely shared. So, in as much as the SCoPEd iteration of this knowledge base becomes a commodity, designed as it appears, for privileged access to the NHS, it may need to be seen as a form of psychotherapathy, potentially delivering an impoverished version of psychopractice.

Taxonomy as a basis for regulation can seem to be a societal disease, the grasping and compressing of the ineffables of desire and anxiety and disappointment into categories and hierarchies. My recent engagement with the climate crisis revealed that there was a hidden dynamic in all this. I had hinted at it a long time ago as ‘glaciation’22 but it merits a bigger role. I came to see that civilizations and their institutions such as psychopractice can be helpfully seen as an accumulation of ‘crystallization’ 23: feeling and perception crystallize as speech; words crystalize as writing, writing crystalizes as books; risk crystallizes as insurance; client behaviour crystallizes as diagnosis; SCoPEd crystallizes psychopractice as ‘standards’.

Today, with crystallisation proceeding at the speed of light via digitisation, taxonomy may be reaching its ultimate limit, with SCoPEd as an example of its paralysing grasp. At our crisis-ridden time, if we want to sustain a fruitful approach to working with the human condition, might not inventing/building/creating ways of contradicting this crystallization be more relevant than reinforcing it as SCoPEd does?

What would that alternative look like?

A very long way off the page of SCoPEd, is self-directed learning. There used to be a university, East London, that ran self-directed education. I taught there, my son did a very good degree by self-directed learning there; it seemed very successful but it disappeared.

I learned my core psychopractice capacity from the self-directed culture of co-counselling 24, and from cooperative experiential work with John Heron 25 and Anne Dickson 26. Building on 25 years as a film director, I learned to facilitate groups as an apprentice, and with Mary Corr and a dozen others generated thriving ‘cooperative enquiries’ 27,28. Around 2000 hours of this self-directed learning, plus self and peer assessment, became enough to begin to work as an independent psychopractitioner, and 28 years of participation in IPN has supported decades of my practice and civic accountability.

I would like to be mistaken but my guess is that this route to psychopractice – where personal development and self-direction sometimes mutate into a vocation as a psychopractitioner – is now closed. SCoPEd lays the foundations for a day job.

From a long-term client perspective, SCoPEd is bad news. Take it down.

Notes/references

1 The Scope of Practice and Education framework (2022) https://www.bacp.co.uk/about-us/advancing-the-profession/scoped/

2 Postle, D. (2007) Regulating the Psychological Therapies – From Taxonomy to Taxidermy, Ross-on Wye: PCCS Books

3 Postle, D. (2012) Therapy Futures: Obstacles and Opportunities (Introducing the PsyCommons), London: Wentworth Learning Resources (available from Lulu.com)4 Postle, D. (2000) Statutory Regulation: Shrink-Wrapping Psychotherapy British Journal of Psychotherapy https://www.academia.edu/26110963/Statutory_Regulation_Shrink_Wrapping_Psychotherapy

5 Postle, D. (1998) The Alchemist’s Nightmare: Gold into Lead – The Annexation of Psychotherapy in the UK International Journal of Psychotherapy 3: 53-83.

6 Postle, D. (1997) How does your garden grow? Counselling News, June: 29-30.

7 Postle, D. (2005) Psychopractice Accountability: A practitioner ‘full-disclosure list’ in Bates, Y. and House, R (eds) Ethically Challenged Professions: Enabling Innovation and Diversity in Psychtherapy and Counselling 172-8, Ross-on-Wye: PCCS Books

8 Independent Practitioners Network, https://ipnetwork.org.uk/

9 Postle, D. (2008) eipnosis: A Journal for the Independent Practitioners Network: Contents http://ipnosis.postle.net/pages/IpnosisContents.htm

10 Casement, A. (1999) Straw poll talkback. BBC Radio 4, 4 September.

11 Postle, D. (1997) How does your garden grow? Counselling News, June: 29-30.

12 Mowbray, R. (1995) The Case Against Psychotherapy Regulation: A Conservation Issue for the Human Potential Movement, London: Transmarginal Press

13 House, R and Totton, N. (eds) (2011) Implausible Professions: Arguments for Pluralism and Autonomy in Psychotherapy and Counselling. 2nd Edn, Ross-on-Wye: PCCS Books

14 Postle, D. (2021) Calling All (UK) Therapists Video London: WLR

15 The Final HPC Professional Liaison Group Meeting (2011) pp 289-294. In Postle, D. (2012) Therapy Futures: Obstacles and Opportunities (Introducing the PsyCommons), London: Wentworth Learning Resources (available from Lulu.com)

16 Virilio, P. (2012) The Administration of Fear semiotext(e): Cambridge Mass. MIT Press

17 Partners for Counselling and Psychotherapy (2023): response to January 22 iteration of the ScoEd framework https://www.partnersforcounsellingandpsychotherapy.co.uk/pcp-response-to-january-2022-iteration-of-the-scoped-framework/

18 The Person Centred Association (2023) Welcome and ScopEd updates and info-where next? https://www.the-pca.org.uk/blog/welcomeandscoped.html

19 ScopEd Impact Assessment (2022) https://www.bpc.org.uk/download/8155/Final-Report-on-the-Impact-Assessment-of-the-SCoPEd-Framework-December-2022.pdf

20 Wampold, B., E. (2001) The Great Psychotherapy Debate, Ch. 8: 2020, London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

21 A judge sentences unqualified psychiatrist Zholia Alemi to 7 years in jail but for 22 years the psychiatrists she worked alongside apparently failed to notice that she was as effective, or ineffective, as they were. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/feb/28/judge-jails-fake-nhs-psychiatrist-and-criticises-abject-failure-of-scrutiny

22. Postle D. (2014) The PsyCommons: Professional wisdom and the Abuse of Power p16-17 Asylum Spring

22 Postle, D. (1994) The Glacier Reaches Edge of Town. Self and Society 23(6): 7-11.

23 Postle, D. (2021) The End of Progress Self & Society Vol 49 No1 Spring, Podcast version: https://soundcloud.com/denis-postle/the-end-of-progress

24 Co-counselling International (UK) http://www.co-counselling.org.uk/

25 Heron, J. (1996) Cooperative Inquiry: Research into the Human Condition, London: Sage

26 Dickson, A. (1985) The Mirror Within: A New Look at Sexuality London: Quartet

27Postle, D. The Nuclear State (1982) Video Crucible: Science and Society, ATV https://vimeo.com/576904068

28 Spencer A. Postle, D. (1998) From Survival and Recovery to Flourishing: a residential co-operative inquiry, London: Counselling News

You must be logged in to post a comment.